by Paul Julian Smith

From Film Quarterly Summer 2007, Vol. 60, No. 4

Director, screenplay: Guillermo del Toro. Producers: Bertha Navarro, Alfonso Cuarón, Frida Torresblanco, Álvaro Augustin. Director of photography: Guillermo Navarro. Editor: Bernat Vilaplana. Music: Javier Navarrete. © 2006 Estudios Picasso, Tequila Gang, Esperanto Filmoj. U.S. distribution: Picturehouse Entertainment. DVD: New Line Home Video (U.S.), Optimum Home Entertainment (U.K.).

Two films recently coincided on the awards circuit. Alejandro González Iñárritu’s Babel (2006) and Guillermo del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth are both the product of transnational Mexican auteurs. But while the former is global in its ambitions (embracing ostentatiously diverse locations from California to Japan via Morocco), the latter is notably local in its scope (set in a precisely delimited place in the post-Civil War Spanish countryside). Moreover, as González Iñárritu’s ambitions become more global, so the morals of his features become more banal. While Amores perros (2000) was a subtle and moving exploration of love and loss, precipitated by an all-too-believable car crash in Mexico City, Babel simply suggests the commonplace that communication is difficult among people of different cultures. Babel‘s narrative is, furthermore, triggered by a random shooting that is insufficient foundation for the huge, unwieldy structure it is made to support.

With Pan’s Labyrinth, however, writer-director Guillermo del Toro has built on his proven skills in fantasy (Hellboy in 2004) and Spanish history (The Devil’s Backbone from 2001) to produce a work that is at once a logical development of his artistic trajectory and a wholly unexpected masterpiece from a director identified with such low-status genres as horror. Perfectly realized within its self-imposed limits of time and space, Pan’s Labyrinth has wider implications for the key questions of nationality, gender, and identity than the bloated, star-studded excess of Babel. And in the technical perfection of its plotting, shooting, and cutting (not to mention its meticulous art design and expert animatronic and digital effects), it suggests a new model for world cinema production.

The trend for major directors to make films outside Mexico (Alfonso Cuarón’s Children of Men [2006] is also cited in this context) has of course been controversial. Mexican critics such as Gustavo García have decried a “Mexican cinema in exile.” Del Toro himself, on the other hand, has spoken of film as “Esperanto,” a universal language which, ironically, would seem to be one answer to the supposed problem of non-communication between cultures at which Babel gestures so showily. As we shall see, del Toro’s practice is a valuable example of transnational cooperation. Eluding nativism (shooting “in exile”), he also avoids facile multiculturalism, engaging deeply with the culture, history, and cinema of his host country. When accepting several awards for Pan’s Labyrinth at the Spanish Oscars or Goyas (where his feature was accepted without controversy as a “Spanish” film) he proclaimed: “¡Viva México y viva España!” This is no facile slogan. Rather it should be taken in the context of del Toro’s vindication of the Spanish Civil War as an event of vital interest for the Mexico that welcomed so many exiles from the conflict. Far from reveling in Babel-style non-communication, Pan’s Labyrinth reveals that, given sympathy and attention, films based on local events can have immediate and profound significance for global audiences.

Pan’s Labyrinth begins with a blank, black screen. We hear the sound of feverish panting and the humming of Javier Navarrete’s haunting theme. Titles briefly set the scene: it is Spain in 1944 and guerrillas are holding out in the woods against the triumphant Franco regime. In close-up we see the source of the labored breathing: as time runs backwards, a trickle of ruby-red blood retreats into the nostril of white-faced, black-haired Ofelia, the child protagonist played by extraordinary newcomer Ivana Baquero. Cinematog-rapher Guillermo Navarro’s camera, already restlessly mobile, plunges into her eye and the first fantasy sequence. The voiceover tells the ancient legend of a Princess, exiled from her underground realm, who will return to be with her father the King when she finds a portal to her lost home. The tiny figure of the Princess (Ofelia) descends the staircases of a vast fantasy set.

The screen flares up to white and the camera swoops over bombed buildings. A wide shot of a ruined bell tower shows the famously devastated village of Belchite, a drawing of which appeared on the cover of the Francoist magazine Reconstrucción as early as 1940. (The village, an uncanny tourist attraction, remains ruinous even today.) Ofelia and her sickly pregnant mother (the convincingly distressed Ariadna Gil) are traveling by official car (a Fascist symbol is prominently painted on its side) to a remote outpost. Here the girl will meet her repellent stepfather (Sergi López), a Francoist captain sent to fight the guerrillas. As mother Carmen stops the car to vomit by the road, daughter Ofelia comes face to face with a stele carved with a mysterious figure and replaces a piece of the carving she has found on the forest floor. She is rewarded with her first glimpse of this magical place’s genius loci: a chattering stick insect she identifies as a “fairy.” Soaring behind the buzzing beast, the camera follows it and the car to the new family’s fateful meeting at the decrepit mill that serves as the Francoist military headquarters.

Allusions to The Spirit of the Beehive (top left) and to Diego Velasquez, Old Woman Cooking Eggs (1618; bottom left), oil on canvas, National Gallery of Scotland © 1973 Elílas Querejeta Producciones Cinematográficas S. L. © 2006 Estudios Picasso, Tequila Gang, Esperanto Filmoj

What is clear from this opening sequence is an extraordinary fluidity of movement between fantasy and reality. While the plot is placed quite precisely in a historical moment with which few outside Spain are likely to be familiar (who knew that anti-Francoist resistance continued long after the Civil War ended?), the material effects of that desperate moment (the bloodied bodies of children) are juxtaposed with, are indeed inextricable from, the fantastic realms into which the imagination retreats when confronted by real-life horror.

Moreover there are very precise Spanish references here, and not just in the expert art design with its reference to a famously devastated village. Ofelia’s mother scolds her daughter for reading fairy tales, telling her they will curdle her brain. It is a charge repeated throughout the film and one highly reminiscent of Spain’s national narrative, Don Quixote, in which fantasy literature also transforms an outcast’s experience of the mundane into the fantastic. It may be no accident that the film’s principal location (built like all the sets to del Toro’s precise specification) is a mill, albeit one deprived of the giant sails which gave rise to the knight’s most famous exploit.

The replacing of the missing piece of the statue is a yet more precise reference. Spain’s most famous art movie, Víctor Erice’s The Spirit of the Beehive (1973), also set in the devastated countryside after the Civil War, confronts a dark-eyed girl (Ana Torrent) with nameless horrors. Ana faces not a faun but Frankenstein’s monster, whom she has seen in a makeshift village cinema. One typically unsettling sequence has Ana, in her schoolroom, replace a missing part in a human manikin. As in the case of Ofelia, her distant sister in Spanish cinema, the missing piece is the eyes. Del Toro thus not only replays Spanish history in a Mexican mode he has perfected elsewhere; he also remakes Spanish cinema by transforming Erice’s austere and minimalist drama with gorgeously crafted mise-en-scène and deliriously inventive camerawork.

Preliminary drawing of the mill Courtesy of Optimum Home Entertainment. © 2006 Estudios Picasso, Tequila Gang, Esperanto Filmoj

In spite of the frequent accusation that democratic Spain has turned its back on a traumatic history, wedded to a “pact of forgetting” between victors and vanquished, Spanish cinema since The Spirit of the Beehive has in fact frequently returned to the scene of Franco’s crimes. Disturbingly, as those crimes have receded in time, the treatment has become progressively trivialized. Several films have shown the post-war period (known in Spain as the “years of hunger”) through the eyes of improbably cute kids (as in Secrets of the Heart [1997] or Butterfly’s Tongue [1999]). Others deploy retro wardrobe to turn the 1930s into expertly dressed sex comedy (the Oscar-winning Belle Epoque [1992]) or the 1940s into a sporting match between Fascists and guerrillas (the soccer-themed The Goalkeeper [2000]). Only del Toro, a supposed outsider, has managed to use the child-witness device, now so hackneyed, without a trace of sentimentality. And only he has been able to make use of an extraordinarily handsome mise-enscène in such a way as to reinforce rather than reduce the horrors of history. In doing so he closely coincides with current trends in Spain, where a “Law of Memory” on the legacy of the Civil War has been bitterly debated and where mass war graves are only now being disinterred, a spectacle del Toro himself, master of the horror genre, might hesitate to depict.

When we move to the interiors of the mill, the main set, golden light slants over dark brown wooden furniture. Elderly women, overseen by steely housekeeper Mercedes (a Maribel Verdú unrecognizable from her role as the sexy wife in Cuarón’s And Your Mother Too [2001]), chop root vegetables or gut rabbits. It is a scene and an aesthetic reminiscent of Velásquez (for example, Old Woman Cooking Eggs in the National Gallery of Scotland), which is frequently reproduced in Spanish period pictures. While local directors have often been content with this picturesque art design, del Toro combines it with more disturbing and ambitious non-naturalistic elements. As mother and daughter hug in their shadowy bedroom (the warm brown palette of day has shifted to the chilly blue of night), Ofelia tells her unborn brother the story of a miraculous flower that blooms every morning. In a single, extraordinary shot del Toro tilts down to inside the mother’s womb, where we see a golden fetus mutely listening, and pans right to the fantastic blossom atop a mountain of thorns. Suddenly the stick insect, clicking and clucking, intrudes into the fantasy landscape and we follow it back to the bedroom where it transforms itself into the slightly sinister fairy of Ofelia’s imagination.

In its stress on a world of women (of mothers, daughters, and housekeepers) wholly separate from that of men, Pan’s Labyrinth is clearly commenting on gender relations. Captain Vidal, the stepfather, embodies a masculinity so exclusive it barely acknowledges the existence of the feminine. Welcoming his pregnant wife and stepdaughter to the mill he addresses them in the masculine plural form (“Bienvenidos”) on the assumption that the unborn child, his true priority, is a boy. As he brutishly announces, a son must be born where his father is, even if this endangers the life of the mother; and, in childbirth, the mother must be sacrificed to ensure the survival of the son who will bear the father’s name. His misogyny will prove his undoing: Mercedes, dismissed as “just a woman,” is in league with the guerrillas and will conspire against her tyrannical master under his very nose.

Del Toro suggests that this fantasy of pure male filiation, without the intercession of women, is fundamental to Fascism. Vidal’s fetishistic attention to uniform (black leather boots and gloves, sometimes clutching a girl’s small white hand) and his amorous investment in the tools of torture (“With this,” he gloats, “we will become intimate”) suggest a fatal narcissism which is as much libidinal as it is political. Vidal’s scenes with housekeeper Mercedes have an icy erotic menace. And it is not just sex that is perverted here. In a time of terror, nature is decidedly unnatural: Ofelia describes her mother as being “sick with baby” (pregnancy will prove a mortal burden); and the verdant landscape (shot in national parks in the region of Segovia) hides blasted trees and monstrous toads. There is no sense of the rich sensuality of nature embodied by the mythical Pan of the film’s English title.

HISTORY, HORROR, AND MAGIC IN PAN’S LABYRINTH Parallel to reality © 2006 Estudios Picasso, Tequila Gang, Esperanto Filmoj

It is after Vidal’s first act of shockingly graphic violence (the stabbing to death of a rabbit-hunter in the face) that del Toro cuts to Ofelia’s first visit to the fantasy world and her meeting with the ancient, creaking Faun that gives the film its Spanish title, El laberinto del fauno. Del Toro is perhaps suggesting here that fantasy is somehow proportionate to or compensatory for the horror of the real. But Ofelia is not a witness to the stabbing. Indeed, although it is tempting to describe hers as the guiding point of view in the film, like Ana Torrent’s character in The Spirit of the Beehive, there is a great deal that she does not see. There are, indeed, gaping holes in the plot where elements first presented as fantastic are later revealed to have empirical presence in the real. What is the source of the mandrake which Ofelia places beneath her mother’s bed and the Captain later discovers, if it is not, as we are shown, given to her by the Faun? How does Ofelia escape a locked room armed only with the chalk that magically creates doors in the walls or floor? The fact that we experience no sense of discontinuity of perspective throughout Pan’s Labyrinth, seduced by its expert plotting and pacing, is a tribute to del Toro’s mastery of story and technique.

Typically del Toro uses effortless parallel montage to interweave narrative threads. Thus as Ofelia, a new Alice, sets out on the first task she has been set by the Faun (a muddy descent to the slimy toad deep under a tree), del Toro crosscuts to the Captain riding out with his men in pursuit of the guerrillas and, later, to a lavish dinner party (the guests’ umbrellas open like small black bombs). Here the Captain announces to his guests: “I want my son to be born in a new clean Spain.” The obsessive abjection of the fantasy world (Ofelia’s snow-white skin is covered in slime and mucous, her shiny patent shoes and prim party dress caked in mud and drenched by rain) might be read as del Toro’s critique of the equally obsessive hygiene of the real-life realm of Fascism.

Unsurprisingly, Ofelia is placed in a bath on her muddy return. Del Toro tilts down from the tub to show her descending the fantasy staircase to the Faun’s lair, once more in a single shot. This technique of the masked cut is vital to the fluid texture of the film: the camera is always tracking behind tree trunks only to emerge unexpectedly in another place, another time. Sound bridges serve the same purpose. The Captain’s traditional songs played on a wind-up gramophone (one, incongruous in this damp, dark Northern setting, is called “Gardens of Granada”) are first sourced in his all-too-real bedroom but are held on to play over scenes set in Ofelia’s fantasy chambers. The clucking of the fairy-stick insect is made to merge with the ticking of the Captain’s stopwatch.

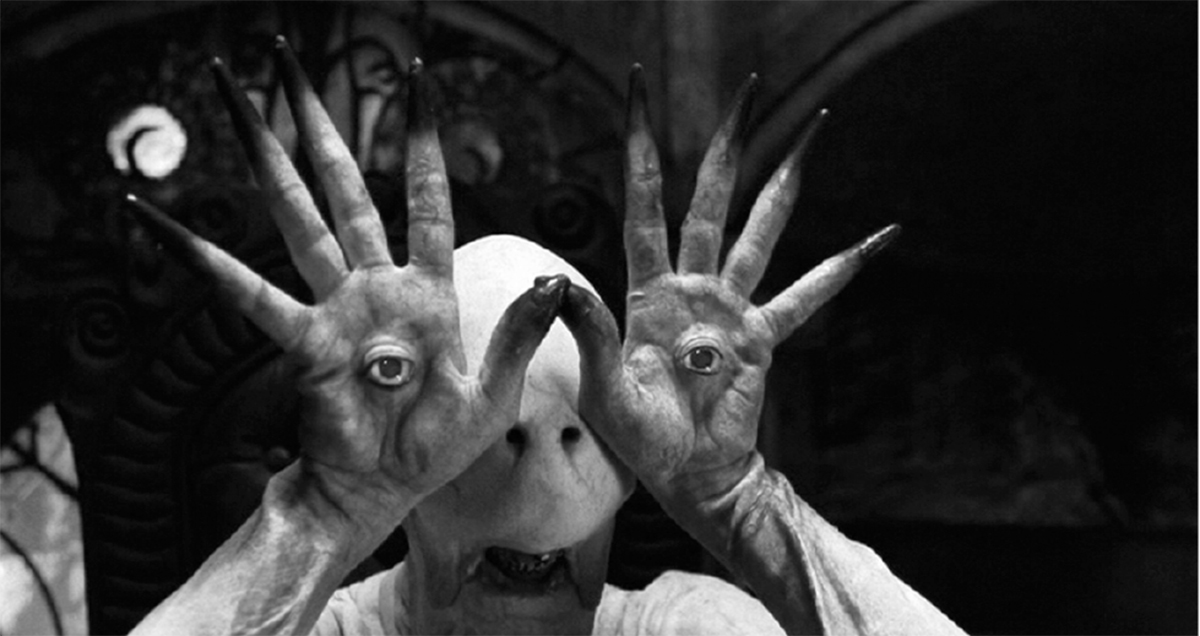

The intricate parallel plotting, by del Toro himself of course, heightens or tightens this tense and intense connection. Ofelia must retrieve a key from a viscous ball vomited by the toad, just as Mercedes must guard, in real life, a secret key to the storeroom. Or again, Ofelia gets hold of a fantasy dagger in her second trial, just as Mercedes keeps in her apron a knife with which she will slice open the Captain’s cheek (“You’re not the first pig I’ve gutted”). Sometimes fantasy anticipates reality: a bloody stain spreads on the pages of Ofelia’s magical book, just as (in the next shot) her mother’s nightdress is drenched with blood as she nearly suffers a miscarriage. But at others it runs parallel to reality: Ofelia places under her mother’s bed a mandrake root, bathed in milk and fed on blood, which mirrors the real-life fetus that drains the mother of life. The sinister faux baby squirms and squeals when thrown on the fire. Finally, fantasy may follow reality. A luscious feast of blood-red berries and jellies, guarded by Doug Jones’s truly disturbing Pale Man (his eyeballs inserted into the palms of his hands), echoes the real-life dinner for the Francoist victors presided over by the sadistic Captain, which we have already been shown.

Fauns and other creatures. Top right: The Chronicles of Narnia The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe (Andrew Adamson, 2005). Bottom right: Hellboy (Guillermo del Toro, 2005) © 2005 Disney Enterprises Inc., Walden Media LLC © 2006 Estudios Picasso, Tequila Gang, Esperanto Filmoj © 2004 Revolution Studios Distribution Company

Ofelia’s mother tells her daughter that life is not like the fairy stories with which she is obsessed. Complicating the relation between life and art and avoiding simple dichotomies, del Toro suggests, disturbingly, that it is. Francoist Spain is a world of suspended time, symbolized by the Captain’s stopped watch, which his father smashed at his moment of death. The Faun’s evocation of the fantastic realm to which Ofelia will return as Princess is also fixed and frozen: however many centuries pass, still it will remain the same. Del Toro’s grotesque wooden creature (an alarmingly uncomfortable prosthetic design encasing Doug Jones, the piscine Abe Sapien of Hellboy, once more) could hardly be further from another recent film faun, the friendly, furry Mr. Tumnus (James McAvoy) of The Chronicles of Narnia (2005), a project del Toro says he was offered but turned down. When, late in Pan’s Labyrinth, Ofelia rushes to embrace her Faun, viewers will feel distinctly uncomfortable. While Captain Vidal is obsessed with his baby son’s safety, the Faun has more sinister plans: Ofelia’s third task will be to hand over her brother for sacrifice.

In the final shot of Pan’s Labyrinth, blood leaks from Ofelia’s nostril, repeating and reversing the first image we saw one hundred minutes earlier. The haunting hummed lullaby, whose words we are told are long forgotten, is heard once more. Del Toro’s camera swoops up over the tragic tableau (shot like much of the film in unnervingly thick shadow) but dissolves to a shot of the dead tree, now with a magical flower blossoming on its sterile bough. The eternal stick insect buzzes by. While the suggestion of innocent sacrifice and redemption is disturbing, the image remains a worthy symbol of del Toro’s achievement. He has taken a tiny terrible moment in Spanish history and translated it into a masterful film with which global audiences and prize juries alike clearly feel a deep and emotional connection. It is a feat of cinematic Esperanto that transcends both the supposed exile of Mexican cinema and the alleged non-communication of national cultures.

PAUL JULIAN SMITH is the Professor of Spanish in the University of Cambridge. His most recent books are Spanish Visual Culture: Cinema, Television, Internet (Manchester University Press, 2006) and Television in Spain: From Franco to Almodóvar (Boydell and Brewer, 2006).

A world of women but no mention of Lorca; the final stanza one of female/child sacrifice: hardly ‘without a trace of sentimentality’.

Thanks for your comment on my piece. I hadn’t thought about the Lorca connection. I’m not sure if del Toro is really aware of the Spanish literary tradition as he is with Spain’s film history. Interesting though that in Bernarda Alba the matriarch is the monster where here it’s the father. As for sentimentality, I take the final sequence to be Ofelia’s definitive entrance into the realm of the fantastic (through death). I guess I found it emotionally engaging but not sentimental in an intrusive or manipulative way.

Pingback: Fantasy Assignment #1 « The Exploration of Science Fiction & Fantasy

I do have to say that while I agree with Moule that Lorca is present in Laberinto as much as Cervantes is — though I thought of Yerma first myself — I agree with you that it isn’t at all sentimental.

Rather I see it as a reaction to the sentimentalizing of feminine sacrifice that Western media (secular no less than religious) is rife with — and also to the blithe dismissal of sacrifice as either ennobling in itself, without considering the bloody costs (typical of the religious take, and the hallowing of maternal martyrdom not simply by Catholicism these days), or as simply a motivating/catalyzing factor for masculine vengeance and violent action (pretty much all of secular pop culture, unfortunately!)

So, I see it (now, since I didn’t watch it when it came out, because I was entirely misled as to what it was by all the reviews I saw at the time, and only just discovered this illuminating one after having discovered del Toro this past summer, as an old kaiju-&-mecha fangirl) as a syncretic response primarily to other major pop cultural phenomenon at the time, “The Lion, The Witch & The Wardrobe” — the Chronicles of Narnia being a saga about little kids, with much of the PoV being a little girl’s, going to dangerous otherworlds, trusting mystical powers, and ultimately dying and going to Heaven while their bodies are killed in a train-wreck — and “V for Vendetta”, a story of a slightly older girl’s being turned into a weapon of creative destruction in a fight against a fictionalized British fascism — with a strong dash of cold water on the “dead mothers” trope as employed against Natalie Portman earlier in “Revenge of the Sith,” which is how the invocation of “David Copperfield” in the scene where Vidal crunches Ofelia’s hand because it’s the “wrong” one, gets into the connective tissues of the tale.

Although I don’t have a direct authorial citation, the way I do for the influence of Charles Dickens in “Laberinto” from del Toro’s DVD commentary track, for Lorca, it’s obvious to me that Ofelia’s mother’s taking of her books and her stepfather blaming them for corrupting her mind — in a mill, no less! — is as much a reference to the Knight of La Mancha as it to those who “grind your bones to make our bread”, with brother Peter in the forest and his Lost Boys vainly tilting at engines too great for frontal assault, and the girls as Jacks stealing away the Giant’s treasure, as much as they are Ariadnes finding a path that doesn’t lead to more sacrifices to the Minotaur–

Because the Pale Man’s seeing-stigmata — and all the “eyes in hands” throughout del Toro’s films, just like the use of green and gold as conflicted Hope and Triumph symbols, must surely be influenced by Sor Juana Inés’ “Verde Embeleso,” just as the “fire without smoke” (paired with smoke as false signal) is a recurring theme ever since Devil’s Backbone, where “Incendio” is recited at a key moment early on, to be matched with a verse from Tennyson’s “In Memoriam” — which he reiterated in the same narrative position, in Hellboy 2: The Golden Army!

But with him growing up surrounded by Spanish Republic expats talking about Their War, as he describes in the commentary track to Devil’s Backbone, I don’t doubt his familiarity with the literature of the era, at all.

By the way, I need to thank you, with EXTREME gratitude, for providing, via the identification of the opening setting as Belchite, the Key I needed to make sense of my vague cognizance of the way that del Toro has been tying England (and England’s colonies) and Spain’s empire together in his stories even before Laberinto, and even more strongly since–

All my complicated chaining of heraldic symbology and film and historical references to alliances going back to Outre-mer, months of study and contemplation, all of it swept aside with the single proper name — ARAGON!

And thus the strange way that the conjoined double-lions of the wall-safe mantlepiece — which echoes the earlier hidden safe of Backbone — become 3 lions, if you don’t look at it too closely and don’t worry about consistency in the lines of the art — because the lions of Castile & Léon have been family with the Plantagenet lions for a very long time, and the ties have been renewed again and again, even if the thrones of England and Spain went to war almost immediately thereafter, nominally over the disdain for a queen and a faith, but certainly equally over the Plus Ultra beyond the Pillars of Hercules!

Pingback: Childhood in Post-Franco Spanish Cinema | spanishcinephilia

This is a movie with a simple and straightforward plot which contains layers and layers of intelligent writing, metaphors and message.

To speak further about the script will end up in spoilers and that would be pointless since my very purpose writing this review is to encourage people to see it.

This is no small feat, interpreting fantasy as something of a product of a real world, cross-referencing how the child acts to her real surroundings and the “other world”, metaphors that describe the accelerated state of growing up some of us are put through… Incredible. Simple, straightforward yet there is so much to be appreciated.

Those who are saying how it’s predictable and thus not enjoyable, I ask of you, which movie nowadays aren’t predictable? Hell, even 21 grams was predictable but so damned good. It’s not about how it ends, you can always predict how a movie would end if you’ve ever taken a half-decent script writing class or have some common sense. It’s always about how well you tell a story.

I’m grateful there are still directors who aren’t tied down to this new epidemic of including a plot twist simply because they need a plot twist.

Pan’s Labyrinth features some of the best storytelling and attention to detail without being affected by the now ever-popular opinion of cameras having to be put through several technical difficulties to make the shots eligible to be called a brilliant shot.

I am also grateful for them not dubbing it. Watching it in its’ original language is much, much more rewarding even if I had to rely on the subtitles for most of the time.

This is a brilliant movie. Watch it.

Pingback: Pan’s Labyrinth: Disobedient Fairy Tale – Sr. Nerd

Pingback: Gullermo del Toro – Blog

Pingback: Gullermo del Toro – skilfulpapers

Pingback: Filmmaker Guillermo del Toro (detailed topic in Instructions) – skilfulpapers

Pingback: Filmmaker Guillermo del Toro (detailed topic in Instructions) – Blog

Pingback: ‘Busco a mi hija …’: the scandal of the niños robados – Europa geht durch mich

Pingback: Die Vaterfigur in „El Laberinto del Fauno“ – LAMelodram

Pingback: Inwiefern ist das Melodram im Fantasyfilm enthalten? – LAMelodram

Pingback: 260. पैन की भूलभुलैया (#146) - उसामास्पीक्स

Pingback: Elliot Page’s 16 Best Movies and TV Shows, Ranked by Rotten … – MovieWeb – Shining a Spotlight on the Latest in News, Entertainment, and Lifestyle at Spotlight.ink

Pingback: Les 16 meilleurs films et émissions de télévision d'Elliot Page, classés par Rotten Tomatoes

Pingback: Las 16 mejores películas y programas de televisión de Elliot Page, clasificados por Rotten Tomatoes