by Rob White

FILMS REVIEWED:

A Prophet (Jacques Audiard)

A Serious Man (Ethan Coen, Joel Coen)

A Single Man (Tom Ford)

Chloe (Atom Egoyan)

The Time That Remains (Elia Suleiman)

Around a Small Mountain (Jacques Rivette)

SPOILER NOTE: This report does not contain major spoilers.

Trip To The Festival

One of the London Film Festival’s participating cinemas is the Rio in Dalston, a district of the Borough of Hackney in the East End. This arthouse establishment is part of a cluster of alternative venues that have recently made the neighborhood fashionable.

Just behind the Rio is the Vortex Jazz Bar, relocated from Stoke Newington, a mile away; a few doors to the north is the Dalston Superstore, offshoot of a south-of-the-river gay nightclub, Horse Meat Disco; behind the nearby mall is Café Oto, a cutting-edge space for experimental and electronic music. Locally there is talk of a Bohemian migration from nearby Shoreditch and certainly I have noticed an increasing number of young men with cavalier mustaches and rocker quiffs.It must be time for the artists and fashionistas to uproot when gossip columns report that a young prince of the House of Windsor likes to party in Shoreditch. But Dalston has had one art-world connection for more than three decades. Across the street from the Rio is the no-frills restaurant where Gilbert and George are regularly seen at suppertime.

Just behind the Rio is the Vortex Jazz Bar, relocated from Stoke Newington, a mile away; a few doors to the north is the Dalston Superstore, offshoot of a south-of-the-river gay nightclub, Horse Meat Disco; behind the nearby mall is Café Oto, a cutting-edge space for experimental and electronic music. Locally there is talk of a Bohemian migration from nearby Shoreditch and certainly I have noticed an increasing number of young men with cavalier mustaches and rocker quiffs.It must be time for the artists and fashionistas to uproot when gossip columns report that a young prince of the House of Windsor likes to party in Shoreditch. But Dalston has had one art-world connection for more than three decades. Across the street from the Rio is the no-frills restaurant where Gilbert and George are regularly seen at suppertime.

No one seems perturbed by the influx of new-style beatniks and disco devotees. It adds an extra accent to a long-established cultural mix. All along the Kingsland Road, on which the Rio is situated, are Turkish ocakbasi (barbecue) joints, where kebabs are served simply with rice, salad, and piles of bread. Opposite Dalston Kingsland overground station is Ridley Road Market, which is full of African (Nigerian, Somali) and Caribbean food stalls and butchers, some of them halal; goat carcasses are strung up above boxes of every kind of offal, which always put me in mind of Suzanne Vega’s song “Ironbound / Fancy Poultry.” The main intersection is being dug up to construct a new station, to be called Dalston Junction, in time for the 2012 Olympics.

The 76 bus goes to St Paul’s Cathedral. It is a short walk from there to the once-wobbly Millennium Bridge that leads to the hugely popular Tate Modern. This whole bankside area south of the Thames is now full of restaurants and visitor attractions (from the wine-tasting center Vinopolis to Sam Wanamaker’s Globe Theatre). It is a pleasant fifteen-minute walk westward along the river to one of the festival’s main venues, BFI Southbank (formerly the National Film Theatre), built underneath Waterloo Bridge. Its huddled location means it is dwarfed by the Royal National Theatre (Fiona Shaw is appearing in Mother Courage and Her Children), Hayward Gallery (currently hosting an Ed Ruscha retrospective), and Royal Festival Hall (which is preparing to host the London Jazz Festival). It was outside this concrete-and-glass concert hall on the morning of May 2, 1997, that Tony Blair received the crowd’s adulation after the landslide New Labour election victory.

Hungerford Bridge connects the arts village to Charing Cross Station, adjacent to Trafalgar Square and its commemorative statuary. This past summer the artist Antony Gormley presented One & Other in the square’s northwest corner, in front of the National Gallery, utilizing the unoccupied “fourth plinth” (built to hold a statue of William IV that was never sculpted) as a kind of variety stage for members of the public, reflecting (in the name of art) the TV dominance of shows like Strictly Come Dancing and The X Factor. Behind the gallery is Leicester Square, low-rise home to the cinemas where most of the 2009 festival films were screened, October 14-29.

Hungerford Bridge connects the arts village to Charing Cross Station, adjacent to Trafalgar Square and its commemorative statuary. This past summer the artist Antony Gormley presented One & Other in the square’s northwest corner, in front of the National Gallery, utilizing the unoccupied “fourth plinth” (built to hold a statue of William IV that was never sculpted) as a kind of variety stage for members of the public, reflecting (in the name of art) the TV dominance of shows like Strictly Come Dancing and The X Factor. Behind the gallery is Leicester Square, low-rise home to the cinemas where most of the 2009 festival films were screened, October 14-29.

What is happening in Britain at the end of this mild October? U.K. politics are in the doldrums; one quiet news day follows another. According to reports, the government has undertaken a lobbying campaign in Europe aimed at securing the post of President of the European Council for former Prime Minister Blair–in the event that the president of the Czech Republic finally ratifies the Treaty of Lisbon which creates this new office. There is something crazy about this lobbying, given the domestic unpopularity of Blair and his successor, Gordon Brown, but maybe the unpopularity explains a dream logic implicit in the whole business: if Blair were ascendant again, then a return to that bright, euphoric 1997 summer morning might seem feasible.

But nobody expects a Labour victory in the next U.K. general election. It feels like the end of an era and during these uneventful days, I have found myself looking back (after all one does not get to live through many eras). Foreign policy, and foreign invasions, have rightly come to dominate assessments of the New Labour administration; but its initial, mantrically repeated priority was “education, education, education”–which happens also to be a topic which recurred in some of the films I saw at the festival.

Schooling has a small but telling part to play in Jacques Audiard’s A Prophet, which won the Grand Prix at Cannes as well as London’s new award for best film, the glitzily named Star of London. Malik el Djebena is locked up in a French prison for six years.

What he did to deserve this sentence is never explained, but it is implied that an attack on a policeman was involved. Malik is certainly no hardened thug. In the first section of this intense, gripping film, he is approached by Sardinian gang boss César Luciani, who threatens to kill him unless he murders another prisoner. One of César’s underlings shows him how to conceal a razor blade in his cheek, but when it comes to the attack, Malik has to improvise as blood starts to drip from an accidental cut in his mouth. He manages to get the job done, though, with the same fierce determination which sees him, as A Prophet progresses, acquire power both inside the penitentiary and beyond its walls.

What he did to deserve this sentence is never explained, but it is implied that an attack on a policeman was involved. Malik is certainly no hardened thug. In the first section of this intense, gripping film, he is approached by Sardinian gang boss César Luciani, who threatens to kill him unless he murders another prisoner. One of César’s underlings shows him how to conceal a razor blade in his cheek, but when it comes to the attack, Malik has to improvise as blood starts to drip from an accidental cut in his mouth. He manages to get the job done, though, with the same fierce determination which sees him, as A Prophet progresses, acquire power both inside the penitentiary and beyond its walls.

Malik takes prison literacy classes. He discloses that that he had no family around him, that his first school was the “juvenile center” which he left at eleven. Newcomer Tahar Rahim, excellent throughout, says all this with diffidence and unease, as if it implied some kind of wrongdoing on his part. The scene reminded me of one in Michael Mann’s Thief where James Caan as Frank explains to an adoption worker that he was “state-raised” (the phrase, an unfamiliar one to British ears, recurs in Heat). Audiard gives us no more information than Mann does and this is the point: such men are not in the habit of spelling out the pain and abandonment in their childhoods.

Malik takes prison literacy classes. He discloses that that he had no family around him, that his first school was the “juvenile center” which he left at eleven. Newcomer Tahar Rahim, excellent throughout, says all this with diffidence and unease, as if it implied some kind of wrongdoing on his part. The scene reminded me of one in Michael Mann’s Thief where James Caan as Frank explains to an adoption worker that he was “state-raised” (the phrase, an unfamiliar one to British ears, recurs in Heat). Audiard gives us no more information than Mann does and this is the point: such men are not in the habit of spelling out the pain and abandonment in their childhoods.

It turns out that Malik is a gifted student. He surprises César by learning the boss’s Sardinian dialect and as a result he becomes a key henchman. But at those reading classes Malik met Ryad, a Muslim of his own age, who gains Malik’s loyalty in a way that César never does. Later, Malik becomes fascinated by Ibrahim Lattrache, an Arab mobster. When Ibrahim learns of the younger man’s success in the Sardinian gang, he is impressed: “You’ve come a long way! What are you, a prophet?” Malik looks passionately back at him in response to these words and throughout A Prophet, the honorary Sardinian increasingly feels the gravitational pull of Arab identity. When taunted by Muslim prisoners for tribal disloyalty, he insists that his alliance with the Sardinians is just work, just survival–yet despite that, A Prophet is more about exile and belonging than dog-eat-dog rugged individualism. It is unlike a Mann film in this respect. Emphasizing the hold over imagination of religion, ethnicity, and culture, Audiard weaves a thread of reverie into the film by including several fantasy sequences in which Malik is seen in his cell with Reyeb, the man he assassinated with the razor. In place of back story or dialogue which reveals Malik’s inner thoughts, Audiard gives us these morally complex, stylistically bold vignettes of a perversely resilient brotherhood born out of violence and betrayal.

The Coen brothers’ A Serious Man and Tom Ford’s A Single Man have more in common than just their titles. Both films feature middle-aged college professors on the verge of a nervous breakdown; A Single Man is set in 1962, A Serious Man in 1970; both are structured around encounters with two interlocutors (rabbis in the Coens’ film, young gay men in Ford’s); both deal with major emotional distress.

In A Serious Man, Minnesota physicist Larry Gopnik’s wife Judith demands a divorce and sends him packing to the Jolly Roger motel. At the university, a Korean student makes strangely threatening remarks after receiving an “F”; meanwhile, Larry’s tenure committee is receiving anonymous letters about “moral turpitude.” He has health problems and money problems. A man from the Columbia Record Club (which Larry’s son has surreptitiously joined) pesters him on the phone for payment for Santana’s Abraxas. Everything is going wrong in Larry’s life and he turns to the two rabbis for advice. (He tries to see a third, but is refused entry because Rabbi Marshak is too busy thinking.) The first, young and clueless, babbles about a car park; the second tells a story about a dentist who discovers Hebrew text carved inside a patient’s teeth–the lesson, such as it is, being that the meaning of some messages can never be understood.

In A Serious Man, Minnesota physicist Larry Gopnik’s wife Judith demands a divorce and sends him packing to the Jolly Roger motel. At the university, a Korean student makes strangely threatening remarks after receiving an “F”; meanwhile, Larry’s tenure committee is receiving anonymous letters about “moral turpitude.” He has health problems and money problems. A man from the Columbia Record Club (which Larry’s son has surreptitiously joined) pesters him on the phone for payment for Santana’s Abraxas. Everything is going wrong in Larry’s life and he turns to the two rabbis for advice. (He tries to see a third, but is refused entry because Rabbi Marshak is too busy thinking.) The first, young and clueless, babbles about a car park; the second tells a story about a dentist who discovers Hebrew text carved inside a patient’s teeth–the lesson, such as it is, being that the meaning of some messages can never be understood.

A Serious Man is tightly constructed, splendidly acted across the board, and often hilarious. But in its own way it is bleaker than No Country for Old Men, whose depiction of personified evil is offset by an idea of social cohesion–such community may be dying out but it at least exists residually, if only in the sheriff’s successful marriage. In A Serious Man, by contrast, the despair is as expansive as the Midwestern plains; everything is corroded by it. Arrested for soliciting, Larry’s brother cannot contain his anguish one night: “it’s just fucking shit,” he cries out, over and over. Sheriff Bell in No Country for Old Men appeals to a bygone Texan decency, to old-timer goodness and wisdom. Larry is advised at one point: “We’re Jews. We’ve got that well of tradition to draw on.” But A Serious Man seems to have lost any faith in heritage. In an unexplained prologue set in nineteenth-century Poland, a woman stabs an elder in the heart because she suspects him to be a dybbuk (a demon parasitically occupying a living body). At first it looks like she is right because the man smiles wickedly, as if unhurt. Then the blood from the wound starts to stain his shirt and the elder stumbles out into the night. The Coens’ vision of the past is blackly comic and weird, but its slow-bleeding horrors seep out unstoppably into A Serious Man as it moves toward a near-apocalyptic ending. The message carved into the patient’s teeth? “Help me. Save me.”

Tom Ford’s English professor, George Falconer, played against type by Colin Firth, teaches literature in Los Angeles. He is mourning his long-term lover, Jim, who died in an auto accident eight months previously. Unlike Larry, he is not beset by family woes. One early flashback shows him taking a furtive call from Jim’s uncle: George is not welcome at the funeral, but the uncle wants him to know what happened. As George listens, mumbling politely in response, the camera zooms in slowly on Firth’s almost expressionless face. A Single Man emphasizes the surface of things: clothes, color, a demeanor that hides feelings. “I am exactly what I appear to be,” George says later, “if you look closely.” That statement does not mean that, for example, he is not grief-stricken: the film’s second shot is a wrenching dream sequence in which George tenderly kisses Jim as he lies dead by the overturned car. Yet he wears his sorrow minimally and the stoicism is a visible part of his grief, not a reaction against it.

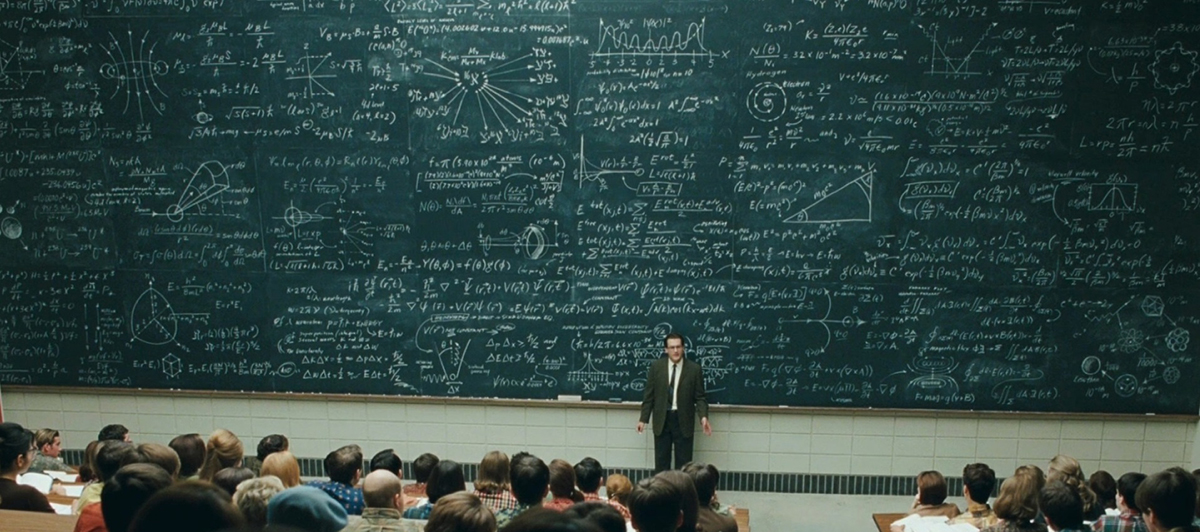

A Single Man co-stars Julianne Moore as Charlotte, a boozy Bohemian neighbor who dotes on George. Her presence recalls both The Hours and Far from Heaven. The more apt comparison is probably with the former: the melancholy and persistent use of flashbacks recalls the alternating day-in-the-life temporalities of The Hours. Although overall Ford’s film suffers in the comparison with Todd Haynes’s reworking of 1950s melodrama, A Single Man uses color flamboyantly in a way that is reminiscent of Far from Heaven. Has any university lecture theater has ever been so elegantly upholstered in moss green as the one in which we see George speak about writing and politics to students dressed exquisitely in duck-egg blue and pale peach?

A Single Man co-stars Julianne Moore as Charlotte, a boozy Bohemian neighbor who dotes on George. Her presence recalls both The Hours and Far from Heaven. The more apt comparison is probably with the former: the melancholy and persistent use of flashbacks recalls the alternating day-in-the-life temporalities of The Hours. Although overall Ford’s film suffers in the comparison with Todd Haynes’s reworking of 1950s melodrama, A Single Man uses color flamboyantly in a way that is reminiscent of Far from Heaven. Has any university lecture theater has ever been so elegantly upholstered in moss green as the one in which we see George speak about writing and politics to students dressed exquisitely in duck-egg blue and pale peach?

Sitting at the front during the lecture is Kenny, in a mohair sweater and tight white jeans, who flirts outrageously with George, suggesting afterwards that they get together one day because “I think you might like it.” The cutting between the two men accentuates the fact that Nicholas Hoult, playing Kenny, is smothered in fake tan. The two of them will later rendezvous off-campus, but not before George has met another Adonis (“you’re better than James Dean,” says George), a Spaniard hanging around a gas station hazed in jaundiced smog–or rather, I should say, in “fake smog,” for this is a highly artificial shot. I found myself wondering if we are meant to connect the tan and the smog, their sickly hues preventing too much of a romanticized response to these encounters–for they are a little poisoned, like everything else in George’s world, by what he has lost.

A debut filmmaker, Tom Ford made his name as the creative director of the Gucci fashion house, which he revitalized. In Chloe, a kind of enchanted stalker movie, at one point we see a bookshelf containing a volume on Gucci next to one on Menachem Begin, and this juxtaposition encapsulates the odd mix of elements in Atom Egoyan’s film.

Julianne Moore plays Catherine, a Toronto gynecologist, married to Liam Neeson’s music professor, David. He is a high-tech educator. His lecture theater seems to have 35mm projection facilities and he is happy to use Instant Messaging to stay in touch with his students. Later, when Catherine confronts him with her suspicion–first triggered by a photo she finds on his iPhone–that he is having an affair with a student, he responds with a justification of his pedagogy: “I make myself available to my students. That’s how I gain their trust. That’s how I teach!” Chloe‘s narrative use of computer technology is notable throughout. Most memorably, Catherine goes into her teenage son’s bedroom where he is video-chatting to his girlfriend, who is breaking up with him. His back is turned–but she can see his mother entering, via the webcam, and hurriedly breaks the connection.

Julianne Moore plays Catherine, a Toronto gynecologist, married to Liam Neeson’s music professor, David. He is a high-tech educator. His lecture theater seems to have 35mm projection facilities and he is happy to use Instant Messaging to stay in touch with his students. Later, when Catherine confronts him with her suspicion–first triggered by a photo she finds on his iPhone–that he is having an affair with a student, he responds with a justification of his pedagogy: “I make myself available to my students. That’s how I gain their trust. That’s how I teach!” Chloe‘s narrative use of computer technology is notable throughout. Most memorably, Catherine goes into her teenage son’s bedroom where he is video-chatting to his girlfriend, who is breaking up with him. His back is turned–but she can see his mother entering, via the webcam, and hurriedly breaks the connection.

Catherine’s suspicion leads her to hire the eponymous prostitute, played ingenuously and skillfully by Amanda Seyfried, as an agent provocateur. (Chloe is, it turns out, a skeptic about the online world. “I hate the Internet,” she says, “nothing is real, nothing is private.”) How far will David go with Chloe’s encouragement? Catherine tries to use Chloe like spyware–a means of gaining remote access to her husband’s desires. But of course things are not so simple as that: Catherine is drawn into a double game. When she is emailed an incriminating photograph, Chloe starts to resemble Michael Haneke’s Hidden.

Catherine’s suspicion leads her to hire the eponymous prostitute, played ingenuously and skillfully by Amanda Seyfried, as an agent provocateur. (Chloe is, it turns out, a skeptic about the online world. “I hate the Internet,” she says, “nothing is real, nothing is private.”) How far will David go with Chloe’s encouragement? Catherine tries to use Chloe like spyware–a means of gaining remote access to her husband’s desires. But of course things are not so simple as that: Catherine is drawn into a double game. When she is emailed an incriminating photograph, Chloe starts to resemble Michael Haneke’s Hidden.

The difficulty with Egoyan’s film is in deciding to what extent it should be taken as a critique of the family’s bubble world–the modernist home, the son’s piano recital, the chic city bars, all the books and machines. Chloe is much more interesting when Catherine is entranced by Chloe and their erotic con trick rather than when she trespasses upon her son’s online intimacies or listens to his cellphone conversation from an upstairs window. The film works best in the mode of Belle de Jour, less well when in the mode of Strangers on a Train. Yet if Chloe sometimes seems too delighted by upper-middle-class Toronto, there remains the fact that at the film’s climax we discover that Catherine and David’s enviable house is flimsier than it appears.

Based on his father’s diaries, Elia Suleiman’s excellent film is a family memoir spanning six decades and set in Nazareth, a Palestinian town which surrendered to Israeli troops in 1948 (an act depicted in The Time That Remains) and was annexed.

Together with other residents, the Suleiman family become Israeli citizens and in one scene we see pupils singing a patriotic song. The song contrasts with the film’s emphasis elsewhere on muteness. In another school scene, a teacher grills young Elia: “Who told you America is colonialist? You can’t say such things in class!” The boy, in navy shorts and light blue shirt, does not answer. As far as we see, the Suleiman family never discusses politics, though a demented neighbor rants drunkenly on the subject. Nevertheless, Elia is later radicalized and deported–we never understand precisely for what reason. When he returns years later, a debonair, sad-eyed man with flecks of grey in his hair (the director plays himself here), he seems to have settled in the taciturn ways of both his parents, though his father Fuad is now dead.

Together with other residents, the Suleiman family become Israeli citizens and in one scene we see pupils singing a patriotic song. The song contrasts with the film’s emphasis elsewhere on muteness. In another school scene, a teacher grills young Elia: “Who told you America is colonialist? You can’t say such things in class!” The boy, in navy shorts and light blue shirt, does not answer. As far as we see, the Suleiman family never discusses politics, though a demented neighbor rants drunkenly on the subject. Nevertheless, Elia is later radicalized and deported–we never understand precisely for what reason. When he returns years later, a debonair, sad-eyed man with flecks of grey in his hair (the director plays himself here), he seems to have settled in the taciturn ways of both his parents, though his father Fuad is now dead.

In a number of late scenes of great poignancy, we see his aging mother sitting on her terrace looking out over the city, impenetrably lost in thought. Near the end of the film, lying in a hospital bed, she communicates with gestures that invoke a whole lifetime.

In a number of late scenes of great poignancy, we see his aging mother sitting on her terrace looking out over the city, impenetrably lost in thought. Near the end of the film, lying in a hospital bed, she communicates with gestures that invoke a whole lifetime.

A ruefully satirical vein of slapstick is important to the technique of The Time That Remains. One striking image occurs in Ramallah, to which the adult Elia has travelled. A Palestinian man talks inconsequentially on a cellphone and as he does so the gun turret of a tank tracks his movement, the barrel just inches from the man’s head. Elia watches speechlessly and blankly from behind a wall. The scene is an absurd reprise of a much more serious one in the 1948 section of the film. Fuad has been arrested by Israeli soldiers and denounced as a rebel by a masked informer. He is himself blindfolded and in a low-walled orchard a soldier puts a gun to his head, demanding information on penalty of death as he counts to ten. Fuad pre-empts him: “ten,” he says, decisively and unflinchingly. The scene culminates with a grim wide shot of Fuad being beaten senseless, but prior to this brutality Suleiman cuts between close-ups of Fuad’s covered eyes and shots of the countryside beyond the wall. This blindfolded vision of a peaceful land is at the heart of the mournful silences in The Time That Remains, and it is perhaps what Elia’s mother is yearning to see as she gazes into the distance.

Concerning a small travelling circus which has rolled into Arras, Jacques Rivette’s latest film is not about education at all, except in the most fundamental sense of bringing out the best in people.

Deadpan, quiet, tender, sometimes aching with sadness, beautiful from start to finish, Around a Small Mountain stars Jane Birkin and Sergio Castellitto as Kate and Vittorio, strangers who meet and begin to talk. (Castellitto is wonderfully fluid and suave, but to my mind Birkin, though jittery and even slightly stilted, is equally persuasive and compelling.) She is returning to the family business which she had to abandon some years earlier after an accident for which her late father blamed her. The enforced departure from the circus haunts her. Vittorio gleans this and seeks to understand what happened. But the incident has changed the course of her life; it is a great and private sorrow. “There are some things I can’t talk about,” she says to her niece. And to Vittorio: “You meddle . . . you hurt me . . . how you hurt me is none of your business.” Still he persists and, together with the artistes, he finds a way to reach her: they stage a show for her, so that she can join the performance if she wishes.

Deadpan, quiet, tender, sometimes aching with sadness, beautiful from start to finish, Around a Small Mountain stars Jane Birkin and Sergio Castellitto as Kate and Vittorio, strangers who meet and begin to talk. (Castellitto is wonderfully fluid and suave, but to my mind Birkin, though jittery and even slightly stilted, is equally persuasive and compelling.) She is returning to the family business which she had to abandon some years earlier after an accident for which her late father blamed her. The enforced departure from the circus haunts her. Vittorio gleans this and seeks to understand what happened. But the incident has changed the course of her life; it is a great and private sorrow. “There are some things I can’t talk about,” she says to her niece. And to Vittorio: “You meddle . . . you hurt me . . . how you hurt me is none of your business.” Still he persists and, together with the artistes, he finds a way to reach her: they stage a show for her, so that she can join the performance if she wishes.

Half-way through the film Kate is seen dying cloth by a stream. Later on she has to return to the atelier where she works with another woman, a clothes designer. They speak about cloth, color, and method: bad ideas may prompt good ones, for example. It is such an arresting, touching scene because it suggests a whole ethos: diligent, artisanal, undemonstrative–but profoundly assured and creative. Around a Small Mountain shares this ethos and it achieves poetic eloquence without the need of grand gestures. A clown routine is seen again and again, each time filmed from a slightly different angle. Many scenes begin with brief, graceful, lyrical tracking shots, which epitomize the complete technical proficiency that makes Rivette’s film so engrossing.

STILLS CREDIT:

Exterior photos by Nina Power. Film stills: Around a Small Mountain, courtesy of London Film Festival. Chloe, courtesy of London Film Festival. A Prophet, courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics. A Single Man, courtesy of London Film Festival. A Serious Man, courtesy of Universal Pictures. The Time That Remains, courtesy of Le Pacte.

Good info